The achievement of high expectations rests on the faculty’s commitment to ensure that each child develops intellectual competence, passion, and power. Teachers working in this manner consistently ask, “Is this a sufficiently high standard for this child?” How do we challenge and scaffold learning rather than overwhelm? It is a fine balance. Academic challenges are set at a personal level for each learner and children are drawn in, through inspiring examples and provocation, to help establish questions and evaluation criteria, critique and sculpt processes, and reflect on results.

Reference books and working portfolios tell the story of children’s thinking…

Evidence of learning is gathered through a child’s drawings, conferences, photographs, log notes, developed writing, demonstrations, displays, prototypes, and formal presentations. Many of these pieces are kept in treasured working reference books and portfolios, accessible for reflection and evaluation by the child, parent, or faculty. Presentation portfolios display the flow and results of a specific study through carefully selected samples from a working collection to tell the story of the child’s progress.

… An historical record for children and families

Archival portfolios house a cross-section of work from the entire year. As children develop their own reference library, it is not uncommon for them to dip back into collections of work –including writing and math journals, word study, or reference books– for ideas, structures, strategies, and formats. Work is not intended to be temporary or disposable at the conclusion of a project, but long-lasting, both physically and in the mind. It is layered, deep, and cyclical. It is not a rare occurrence for a child to emerge, after diving back into earlier work samples, sputtering with a revelation that change has occurred and immense progress was made! “I can’t believe I did that then! What was I thinking?!” (JJ, 2010)

Reflection and self-asessment are keys to the learning cycle

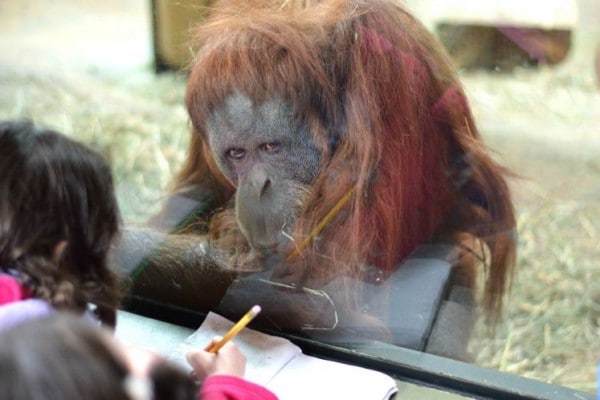

Thinking about our work, its meaning, the quality and quantity of resources used, and decisions made, all become natural and essential ponderings of the learning process. Children engaged in thoughtful experiences are able to generate insights that reach beyond the moment and transform work in the future. They are able to speak lucidly about what has been learned, give reasons for choices, describe intentions, setbacks, and results, and, in many cases, express reasoned views of their own intellectual gains. Evaluation becomes an integral part of the process, a point of pride, as each revelation generates power in the next application. What is learned in one study fuels the next undertaking. The distance we can see, from standing “here” and seeing “there,” is not a measure of deficiency, but the vision of possibility!

Intimate assessment occurs throughout the year

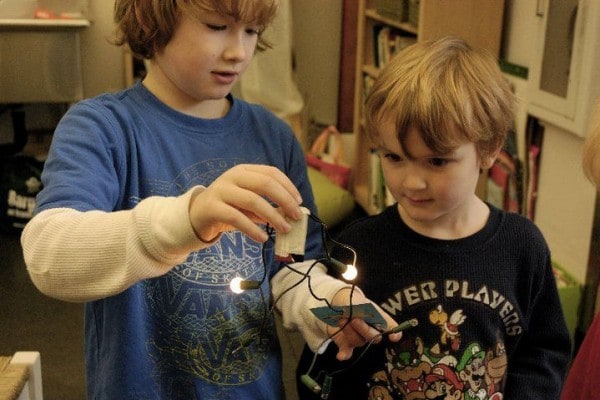

Assessment is on-going and related to what is being learned. Teachers use a variety of strategies to find out what youngsters are learning and how they learn best. They are able to tap into strengths, tackle and bolster areas ripe for growth, and find out where a child may need extra support or a new challenge. The most useful information is garnered as the child sits knee-to-knee with an adult in reading, writing, and math, organizing, practicing, editing, and publishing their work. In that very moment, we can adjust the next comment, question, example, and nudge! In group work, we can observe confusion and insight. We can note depth, nuance, explanation, vocabulary, and application. Astute child-watching is the key!

Our daily work of instruction, assignment setting, and project design is guided by intimate and on-going formative assessment. Close proximity and mutually respectful relationships allow for quick monitoring, deep observation, and telling conversation, creating the ability to make fine adjustments to lessons and plans in order to capitalize on learning opportunities. With watchful eyes for questions, interest, and insight, our small group focus and personal attention, allow us to listen intently, ask probing questions, and offer further instruction.

We listen to and watch children read, pinpointing children’s strategies, knowledge, and skills that are being employed successfully, as well as those that are underdeveloped. In the moment of reading together, we are able to stop and correct a misread word, unwind a misinterpreted passage, or reread a selection with expression. In math, we can watch the child select strategies, assist with computation, and offer visuals to aid in transition from concrete to abstract. We use what we learn through close interaction, work journals, and formative assessment, to design and implement additional supports and practice opportunities for children and families where there is a need for practice at home.

Writing journals are gems, housing drafts, caches of growing vocabulary, polished paragraphs, precious passages, clips, photos, doodles, and lists, provocations for later writing… In writing workshops, we whip out our journals and write!!! We concentrate on traits, drawing from strong literature to set the standards: ideas, organization, voice, word choice, fluency, and conventions. Our writers are introduced to imaginative, persuasive, narrative, descriptive, and expository modes. From pre-writing through drafts and editing, writers continue to evaluate and revise their ideas and structures, adjusting vocabulary, spelling, grammar, and punctuation to aid the reader in making meaning and enjoying the intent of the writer.

Personal reference books house our year-long progress in word study and math. In these logs, children demonstrate their growing understanding of conventions! Concepts in social sciences and sciences are also assessed as children use multi-media approaches to express understanding of factual information and large ideas. Each opportunity opens a window into the question of sufficiency and expected progress for “this” child, and offers an opportunity for next nudges and refinement.

We engage our oldest children in test-taking as an audit, a genre to be learned and a way to think about statistics personally. This first occurs with children at age eight. It also serves as a translation point for some families and for schools the child may attend. It is considered a slice of academic history. (We use a nationally standardized measure, TerraNova, to audit the reading and math skills of our older children. While this measure is a dip-stick in a full-scale audit, it is somewhat external to our daily work.)

Goal-Setting

Goal-setting conferences with children and parents are held with families in the fall. In preparation for that conference, the child self-selects an area or two of focus. Parents and faculty support the child’s intention, designing personal plans. Conferences are opportunities to raise questions, exchange information, assess how learning is progressing, while generating new learning goals, claiming ownership, and scaffolding support. The late spring is a time to celebrate accomplishments and share plans for future learning, completing the cycle and intentionally linking learning, across the summer break, from year to year.

Learner Profiles

Our twice-yearly report is a snapshot of a child’s progress. It is designed to help adults understand where the child is and where the child is going, with brief descriptions of the child’s learning strengths and challenges. The profile is a compilation of two narratives (one written by the child and one written by faculty members), and a description of general development and expectations along with a checklist of specific learning capabilities.

This layout of checklists is used as a continuum of learning. There are four stages for literacy (reading and writing), and for mathematic, scientific, and research elements. There is one overall checklist used throughout the school to indicate development as a learner and community member.

The skills are broad based. They begin with simple forays through guided instruction and become more sophisticated and complex in their application as a child’s thinking develops. The skills, while set out in a linear format here, may not be acquired strictly in that manner by each child. Each child brings background knowledge, interests, motivations, and enrichment opportunities that will influence their learning. We continue to practice and apply skills from earlier levels while setting the stage for introducing and developing the skills in later stages.

And More…

Evidence of growth for each child is made available through portfolio collections, informal conversations, conferences, written reflections in the child’s learning profile, and final narratives. Throughout the year, children invite family members to celebrations of learning. Public demonstrations of learning are time-honored traditions. Communities have gathered for decades to witness recitations and exhibitions, opening the school doors to honor each child. Parents and friends have many occasions to visit the school, pour over portfolios, applaud plays and performances, participate in evening learning events, and admire finished displays. In each case, we encourage parents to talk with the children about the learning behind the exhibition, their choices, accomplishments, and further goals.